Abstract

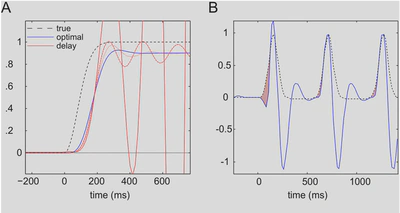

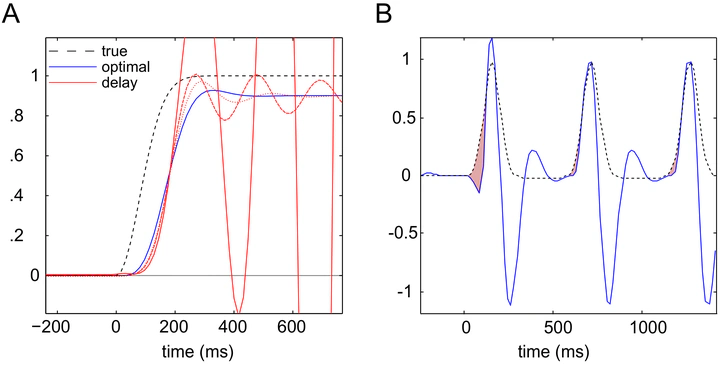

This paper considers the problem of sensorimotor delays in the optimal control of (smooth) eye movements under uncertainty. Specifically, we consider delays in the visuo-oculomotor loop and their implications for active inference. Active inference uses a generalisation of Kalman filtering to provide Bayes optimal estimates of hidden states and action in generalised coordinates of motion. Representing hidden states in generalised coordinates provides a simple way of compensating for both sensory and oculomotor delays. The efficacy of this scheme is illustrated using neuronal simulations of pursuit initiation responses, with and without compensation. We then consider an extension of the generative model to simulate smooth pursuit eye movements in which the visuo-oculomotor system believes both the target and its centre of gaze are attracted to a (hidden) point moving in the visual field. Finally, the generative model is equipped with a hierarchical structure, so that it can recognise and remember unseen (occluded) trajectories and emit anticipatory responses. These simulations speak to a straightforward and neurobiologically plausible solution to the generic problem of integrating information from different sources with different temporal delays and the particular difficulties encountered when a system, like the oculomotor system, tries to control its environment with delayed signals.

Active Inference, tracking eye movements and oculomotor delays

Tracking eye movements face a difficult task: they have to be fast while they suffer inevitable delays. If we focus on area MT of humans for instance as it is crucial for detecting the motion of visual objects, sensory information coming to this area is already lagging some 35 milliseconds behind operational time – that is, it reflects some past information. Still the fastest action that may be done there is only able to reach the effector muscles of the eyes some 40 milliseconds later – that is, in the future. The tracking eye movement system is however able to respond swiftly and even to anticipate repetitive movements (e.g. Barnes et al, 2000 – refs in manuscript). In that case, it means that information in a cortical area is both predicted from the past sensory information but also anticipated to give an optimal response in the future. Even if numerous models have been described to model different mechanisms to account for delays, no theoretical approach has tackled the whole problem explicitly. In several areas of vision research, authors have proposed models at different levels of abstractions from biomechanical models, to neurobiological implementations (e.g. Robinson, 1986) or Bayesian models. This study is both novel and important because – using a neurobiologically plausible hierarchical Bayesian model – it demonstrates that using generalized coordinates to finesse the prediction of a target’s motion, the model can reproduce characteristic properties of tracking eye movements in the presence of delays. Crucially, the different refinements to the model that we propose – pursuit initiation, smooth pursuit eye movements, and anticipatory response – are consistent with the different types of tracking eye movements that may be observed experimentally.