Abstract

During normal viewing, the continuous stream of visual input is regularly interrupted, for instance by blinks of the eye. Despite these frequents blanks (that is the transient absence of a raw sensory source), the visual system is most often able to maintain a continuous representation of motion. For instance, it maintains the movement of the eye such as to stabilize the image of an object. This ability suggests the existence of a generic neural mechanism of motion extrapolation to deal with fragmented inputs. In this paper, we have modeled how the visual system may extrapolate the trajectory of an object during a blank using motion-based prediction. This implies that using a prior on the coherency of motion, the system may integrate previous motion information even in the absence of a stimulus. In order to compare with experimental results, we simulated tracking velocity responses. We found that the response of the motion integration process to a blanked trajectory pauses at the onset of the blank, but that it quickly recovers the information on the trajectory after reappearance. This is compatible with behavioral and neural observations on motion extrapolation. To understand these mechanisms, we have recorded the response of the model to a noisy stimulus. Crucially, we found that motion-based prediction acted at the global level as a gain control mechanism and that we could switch from a smooth regime to a binary tracking behavior where the dot is tracked or lost. Our results imply that a local prior implementing motion-based prediction is sufficient to explain a large range of neural and behavioral results at a more global level. We show that the tracking behavior deteriorates for sensory noise levels higher than a certain value, where motion coherency and predictability fail to hold longer. In particular, we found that motion-based prediction leads to the emergence of a tracking behavior only when enough information from the trajectory has been accumulated. Then, during tracking, trajectory estimation is robust to blanks even in the presence of relatively high levels of noise. Moreover, we found that tracking is necessary for motion extrapolation, this calls for further experimental work exploring the role of noise in motion extrapolation.

- Based on(2012). Motion-based prediction is sufficient to solve the aperture problem. Neural Computation.

- see follow-up on the flash-lag effect:

- Based on Perrinet et al, 2012

- See a followup in Khoei et al, 2017

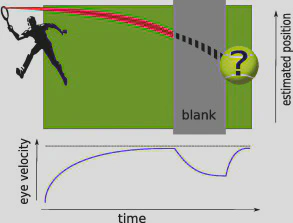

Figure 1: The problem of fragmented trajectories and motion extrapolation. As an object moves in visual space (as represented here for commodity by the red trajectory of a tennis ball in a space–time diagram with a one-dimensional space on the vertical axis), the sensory flux may be interrupted by a sudden and transient blank (as denoted by the vertical, gray area and the dashed trajectory). How can the instantaneous position of the dot be estimated at the time of reappearance? This mechanism is the basis of motion extrapolation and is rooted on the prior knowledge on the coherency of trajectories in natural images. We show below the typical eye velocity profile that is observed during Smooth Pursuit Eye Movements (SPEM) as a prototypical sensory response. It consists of three phases: first, a convergence of the eye velocity toward the physical speed, second, a drop of velocity during the blank and finally, a sudden catch-up of speed at reappearance (Becker and Fuchs, 1985).